Nigel Tao

XZ/LZMA Worked Example Part 1: Range Coding

This blog post is one of a five part series.

- Part 1: Range Coding

- Part 2: A Complete Toy Range Coder

- Part 3: Literal-Only LZMA

- Part 4: Lempel-Ziv, Markov-chain

- Part 5: XZ

Background

XZ is a general purpose compression file format, achieving very good compression ratios (smaller compressed file sizes). Almost always better than gzip/deflate and usually better than bzip2. Newer formats like brotli and zstd are now pretty competitive (and also offer better compression or decompression speeds), depending on your test corpus, but XZ is still widely used.

To be pedantic, XZ is a container format and LZMA is the compression algorithm. The 7z and LZIP file formats aren’t XZ but can also use LZMA.

For further pedantry, XZ is the name of the file format (such files are

conventionally named foobar.xz) but also the name of a git

repository of software that implements

that file format. liblzma and /usr/bin/xz are example artifacts built from

that project.

A few weeks ago, a backdoor was

discovered in

xz/liblzma, targeting SSH servers since sshd can depend on libsystemd can

depend on liblzma. Planting that backdoor exploited the build process, rather

than a weakness in the file format or its C code implementation. Still, xz is

having its 15 minutes of infamy and some of you might be curious about how LZMA

compression actually works. How does it achieve such a good compression ratio?

This blog post series answers that question. We’ll start with range coding.

Notation

Let [lb, ub) denote a half-open numerical range, defined by lower and upper

bounds. It is the set of all numbers x such that (lb ≤ x) and (x < ub).

For example, [0.5, 0.625) are those numbers that are at least ½ and less than

⅝. This example (and most of this blog post) uses base-10 decimal digits (the

digits 0, 1, 2, …, 9), which humans are most familiar with. Computers work

better with powers of two, especially base-2 (binary, bit-based) or base-256

(byte-based). The same [0.5, 0.625) range could also be written as [0b0.1,

0b0.101) or [0b0.100, 0b0.101) or [0x0.80, 0x0.A0).

Let’s also introduce some “no-op underscores”, so that 0.834626841674073 is

the same as 0.83462_68416_74073. These underscores will be most helpful (for

humans) with our base-256 numbers, where each base-256 digit combines two

base-16 (hexadecimal) digits.

The [lb, ub) pair representation is equivalent to a (lb ++ width) pair

representation, where width = (ub - lb). Many discussions of range coding

use the term range instead of width, but range is a reserved keyword in

the Go programming language, so I’m going to use width in my runnable code

snippets.

The width can be implicit. Let «834626841» (which you can think of as a

“digit string” with length 9) denote a lowerBound of 0.834626841 and a width

of 1e-9, where 9 is that string length. That range is equivalent to

[0.834626841, 0.834626842), where the two bounds differ in their last digit.

Note that trailing zeroes matter. «123» and «1230» are different ranges,

even though 0.123 and 0.1230 are the same numbers. Those two ranges have

larger and smaller widths: (0.123 ++ 1e-3) and (0.1230 ++ 1e-4).

Note also that «123» being a “prefix” of «123456» means that the first

range completely contains the second range. The less precise «123» is a

“conservative estimate” of the more precise «123456».

This «123» example range uses decimal digits. Summarizing this blog post

series: the essence of LZMA compression is recording one very precise range

just like this (precise means a large number of digits, so a narrow width), but

using base-256 digits. This very precise range forms the vast majority of the

compressed file’s bytes.

Byms (Binary Symbols)

LZMA is a compression technique combining two steps: (1) “Lempel-Ziv back-references” (I’ll get to those later) with some bureaucratic overhead and (2) range coding. Decoding LZMA involves decoding both steps, in reverse order. Range decoding consumes the compressed bytes (a digit stream, base-256 digits for LZMA) and produces a symbol stream.

Wikipedia’s range coding article discusses a 3-symbol example (‘A’, ‘B’, EOF) but LZMA uses a simpler 2-symbol stream and “End Of File” is often implicit, as the byte length of the uncompressed text (after decoding step 1) is transmitted separately.

A 2-symbol stream is a bit stream but, in order to disambiguate compressed bits-and-bytes from uncompressed bits-and-bytes, I’m going to use “byte stream” for LZMA range coding’s compressed form and “bym stream” for its uncompressed form. Bym is short for “binary symbol” the way that “bit” is short for “binary digit”. There are two bym values. Let’s call them blue (0) and green (1).

LZMA gets good compression ratios because the blues and greens don’t have to be equally weighted in the byte stream. If blues are more common than greens then they can have a shorter representation. For those familiar with Huffman coding, a further advantage of range coding is that the symbol (or symbol-cluster) probabilities don’t have to be a power-of-a-half: 50%, 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, etc. If blues are roughly twice as common as greens then range coding can still represent a 2:1 split (a 67% probability, roughly) fairly accurately.

Treasure Hunting

When decoding LZMA, how does a very narrow range convert into a bym stream?

I’ll use a “treasure hunting” analogy. Suppose that you’re looking for buried

treasure on a 1-dimensional island, aligned west to east. The island is

0.9999 units long, so you can identify any location by a number in the range

(0 ++ 0.9999). You also have a cryptic treasure map: that previously

mentioned, very precise list of digits that locates that treasure. That

location (call it the actual treasure range) is a narrow range.

You can’t keep more-than-four-digit numbers in your head and four is less than the length of the treasure map, so you can’t just head straight to the precise treasure location. Instead, you keep a treasure-prefix range that’s equivalent to a prefix of the treasure map’s digit string. The treasure-prefix range always contains the actual treasure range. You’ll iterate, making progress, and on some iterations you’ll “zoom in”, reading more digits from your treasure map, narrowing the treasure-prefix range’s width by a factor of 10.

You’ll also keep a coverage range that always contains (covers) the entire treasure-prefix range (a range has a width; it’s not a single number) and therefore always contains the actual treasure range.

Each iteration, your coverage range gets narrower. Some arithmetic will tell you how to split your coverage range into two parts, maybe of unequal size, but only one part will contain the treasure-prefix range. Those two parts, west and east, are also labeled blue and green. Each iteration, note whether you’re taking the blue or green branch.

Eventually, you’ll get to the end of the treasure map, but the analogy’s buried treasure chest only held a MacGuffin. The real treasure was the sequence of blue and green byms we made along the way.

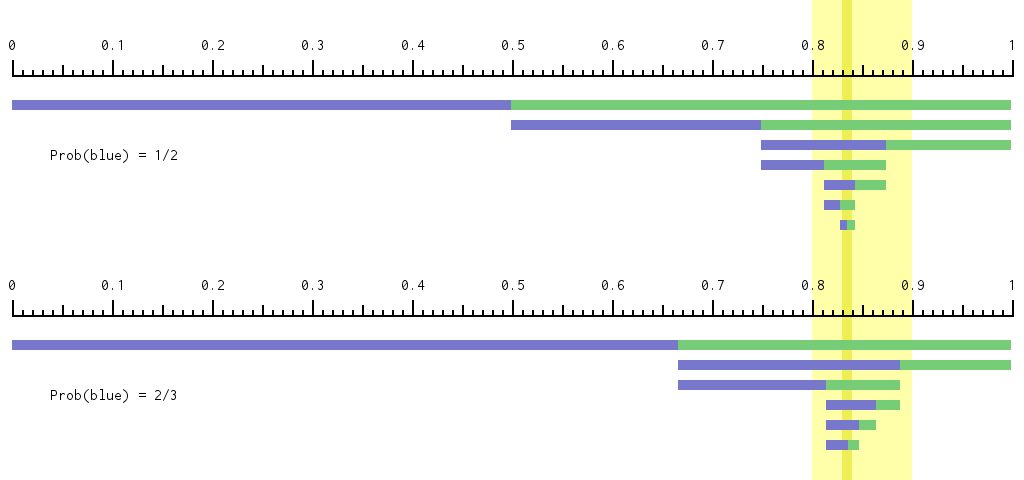

Here’s an illustration of «8» and «83» in light yellow and dark yellow. The

coverage range starts at full width and, at each iteration (row), that range is

split into blue and green parts, at either a 1:1 (top) or 2:1 (bottom) ratio.

At each iteration, whichever ‘b’ or ‘g’ (blue or green) split contained the

yellow treasure range becomes the next iteration’s coverage range. Note that

the bym sequence for «83...» (top: “ggbgbg…” or bottom: “gbgbb…”) depends

on the blue-green ratio (or, equivalently, the “probability” or prediction of

the next bym being blue), not just the «83...» treasure map itself.

In this illustration, the bym stream decoding stops when it becomes ambiguous:

when the «83» dark yellow column crosses a blue-green boundary. In practice,

with LZMA, it’d never get to that ambiguous stage. The coverage, blue and green

widths are always an integer multiple of the treasure-prefix width. We’d zoom

in (making the treasure-prefix width smaller, the yellow column narrower)

whenever the coverage width got too small (as a multiple of that

treasure-prefix width granularity).

Zooming In

At first glance, you’ll need to track four numbers (two pairs of two), since

both the coverage range and the treasure-prefix range have a lower bound and a

width. But also, if you’re limited to four-digit numbers, you can’t just drop

the ‘1’ when you load the ‘5’ from «123456». There’s a transformation that

addresses both concerns.

You conceptually track two lower bounds (coverage and treasure-prefix) but, in practice, only track the difference between them. Remember that the treasure-prefix range is always completely within the coverage range, and the treasure-prefix has non-zero width, so an invariant is that this difference is strictly less than the coverage width.

We can also set the treasure-prefix width implicitly to always be 1 ZLU (Zoom

Level Unit), the granularity that our current iteration is working at. We then

only have to track two state variables: a lower-bound difference (which I’ll

call bits, since it derives from the compressed-data bit stream - the

treasure map; some other range coding implementations call this variable

code) and a width (the coverage width). Both bits and width are integer

multiples of ZLUs.

To start with, set bits the first four digits of the treasure map (actually,

the first five, since the first digit is always zero to simplify the encoder,

see “five digits” below), width to 9999 and the ZLU to 1e-5.

On each iteration, you’ll pick blue or green, then width (the coverage width)

will get smaller. Whenever it gets too small (less than 1000 ZLUs), zoom in

(which makes the ZLU smaller by 10x). Conceptually, zooming in leaves the

coverage range unchanged (it’s 10x as many ZLUs but each ZLU is now 10x

smaller) but narrows the treasure-prefix range by 10x (because we load another

digit from the treasure map; the treasure-prefix width stays at 1 ZLU but a ZLU

is now smaller). It also nudges (by that loaded digit) the bits lower-bound

difference (as measured in ZLUs). In terms of code, zooming in is:

if width < 1000 {

// An invariant is that (bits < width) and so, when limited to

// four-digit numbers, the high (thousands) digit of both bits and

// width must be zero. Multiplying by 10 (and adding up to 9) will

// not overflow.

bits = (10 * bits) + loadNextDigit()

width = (10 * width)

}

The ZLU isn’t explicitly tracked. It’s a useful concept for visualizing and understanding the iterative process but isn’t actually needed in the code.

Decoder

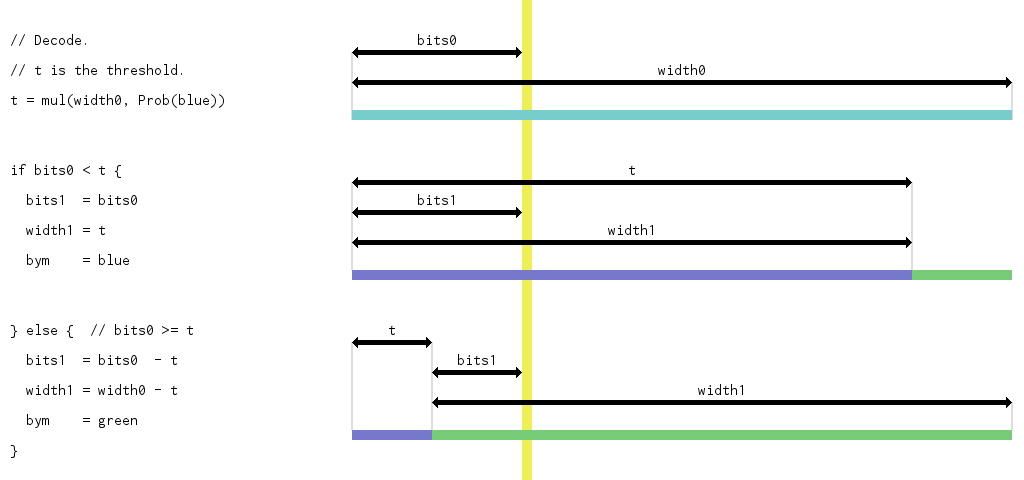

Here’s the decoder inner loop’s code (and a visualization).

// t is the threshold.

t = mul(width, prob)

// Decode the bym.

if bits < t {

width = t

bym = blue

// ¶ TODO: adaptive probabilities.

} else {

bits -= t

width -= t

bym = green

// ¶ TODO: adaptive probabilities.

}

// Zoom in if necessary.

if width < 1000 {

bits = (10 * bits) + loadNextDigit()

width = (10 * width)

}

The mul(width, prob) expression basically multiplies width and prob, but

the mul abstraction glosses away whether prob uses a fixed-point or

floating-point representation.

So far, that probability has been constant and previously agreed on between encoder and decoder. I’ve stuck a couple of “¶” pins in that code for now. We’ll come back to that later.

Encoder

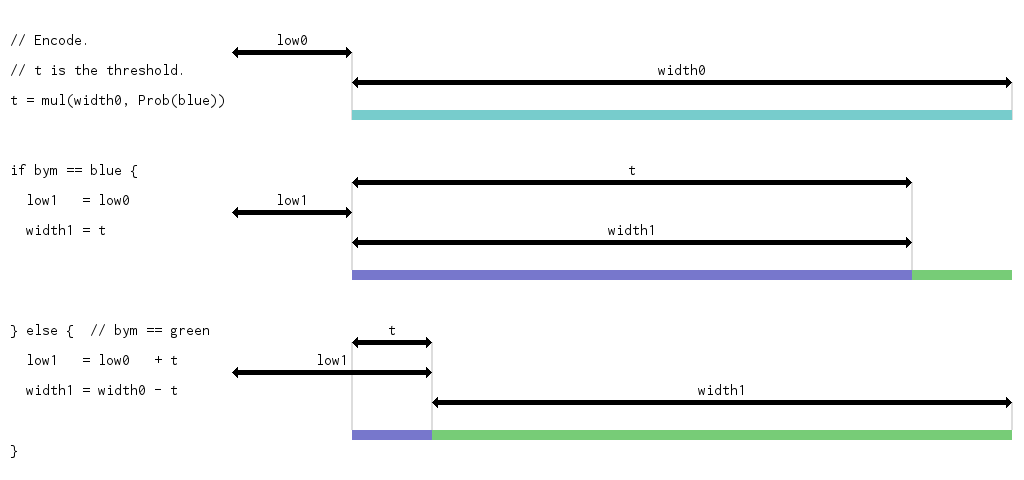

As always, encoding is the opposite to decoding. Decoding starts with the treasure map and produces a bym stream. Encoding starts with the bym stream and needs to produce a treasure map.

Visually, recalling the first image above, playing a sequence of blue and green byms defines a successively narrower range. Setting the treasure range’s lower bound to the final, narrowest row will lead the decoder down the same path (and hence recover the same bym stream).

The decoder basically had two state variables (bits and width) plus the

treasure map itself. The encoder also has two state variables (plus a couple

others; see “N+1 pending digits” below), that are very similar, but slightly

different, so I’m going to call them low and width. In both cases, the

width is the coverage width, which the encoder tracks step-for-step with each

encoded bym the way the decoder updates its coverage width with each decoded

bym.

The encoder’s low is a range’s lower bound, compared to the decoder’s bits

being a difference of two ranges’ lower bounds. The encoder needs to know the

coverage’s lower bound (in ZLUs, modulo 10000) in absolute terms. Its digits

are the ones written out as the treasure map. Here’s the encoder core loop’s

code (and a visualization).

The encoder code is similar to the decoder code. Note especially that both

encoder and decoder zoom in at the same time, after the same number of

iterations. Zooming in happens when the width is small enough, and updating

the width only depends on the threshold (i.e. on the width and prob) and

whether the bym is blue or green. The formula for updating the width does not

depend on the value of the decoder’s bits, other than the decoder uses bits

and t to deduce blue versus green.

// t is the threshold.

t = mul(width, prob)

// Encode the bym.

if bym == blue {

width = t

// ¶ TODO: adaptive probabilities.

} else {

low += t

width -= t

// ¶ TODO: adaptive probabilities.

}

// Zoom in if necessary.

if width < 1000 {

low = shiftLow(low)

width = (10 * width)

}

ShiftLow

The shiftLow function shifts the left-most digit out of the 4-digit low

number and shifts a zero digit into the right-most. For example, with base-10

digits, it turns 5678 into 6780, having “shifted out” the ‘5’ and “shifted in”

a ‘0’. In code:

out = low / 1000

low = (low * 10) % 10000

For base-256 digits and a 4 digit uint32_t low variable, this involves <<

and >> bit-shift operators, hence the “shift” in the function name.

out = low >> 24

low = low << 8

The out digits basically form the treasure map digits. There’s one detail,

though, since we can’t undo writing a digit to the treasure map. Recall that,

at any given iteration, (low ++ width) is a conservative estimate of the

treasure range. If we’ve already written «123» to the treasure map and our

low value is 4996, we don’t want shiftLow to prematurely write out the

‘4’ digit before we’re certain that the treasure range’s lower bound is

0.1234something and not 0.1235something. shiftLow therefore doesn’t emit

the ‘4’ immediately. Instead, it puts the ‘4’ in the encoder’s “pending

digits”, also known as its “cache”. Pending digits are only flushed to the

actual output byte stream when the encoder is certain there won’t be any

overflow that would imply “carrying the 1”. Some code for that is in the

complete range coding implementation in the

next blog post.

There can be more than one pending digit, but if so, all but the first digit must be ‘9’ (with base-10 digits, or ‘0xFF’ with base-256 digits).

It simplifies the encoder if there’s also always at least one pending digit. It’s therefore initialized with a pending digit of zero. That’s why the treasure map always starts with a zero digit (and the decoder starts by reading five digits instead of four, discarding that initial always-zero).

We therefore always have N+1 pending digits, for some non-negative N that counts the number of trailing ‘9’s. The encoder can track this in two state variables: one holds the first pending digit and the second holds N.

Initial Zero Byte

Tangentially, there’s some disagreement whether LZMA decoders should enforce that the initial treasure map digit is zero.

Both

xz

and

lzma-sdk

return an error if that initial byte is non-zero. However, LZIP has an

ignore_marking configuration option that allows for non-zero initial bytes.

Its testsuite/fox6_mark.lz file explicitly tests for this. LZIP files can be

concatenated and this one ‘marked’ the overall file with {'\x00', '\x00', 'm',

'a', 'r', 'k'} in the ignored bytes at positions 0x006, 0x056, 0x0A6, 0x0F6,

0x146 and 0x196. Each sixth of that lz file is otherwise identical.

$ wget https://download.savannah.gnu.org/releases/lzip/lzip-1.24.tar.gz

$ tar xvf lzip-1.24.tar.gz

$ grep -C 5 get_byte.*ignore_marking lzip-1.24/decoder.h

bool load( const bool ignore_marking = true )

{

code = 0;

range = 0xFFFFFFFFU;

// check and discard first byte of the LZMA stream

if( get_byte() != 0 && !ignore_marking ) return false;

for( int i = 0; i < 4; ++i ) code = ( code << 8 ) | get_byte();

return true;

}

void normalize()

$ lzip --decompress --stdout lzip-1.24/testsuite/fox6_mark.lz

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

$ hd lzip-1.24/testsuite/fox6_mark.lz

00000000 4c 5a 49 50 01 0c 00 2a 1a 08 a2 03 25 66 f1 4b |LZIP...*....%f.K|

00000010 78 c5 a2 05 ff 2e e6 d9 d2 20 1a ad 34 f8 e2 1d |x........ ..4...|

00000020 e8 41 36 fa dc 06 69 bb 3c e4 10 34 27 09 eb b3 |.A6...i.<..4'...|

00000030 66 e3 ec 97 ea ae 23 ff fe 8e a0 00 6a cc 50 eb |f.....#.....j.P.|

00000040 2d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |-.......P.......|

00000050 4c 5a 49 50 01 0c 00 2a 1a 08 a2 03 25 66 f1 4b |LZIP...*....%f.K|

00000060 78 c5 a2 05 ff 2e e6 d9 d2 20 1a ad 34 f8 e2 1d |x........ ..4...|

00000070 e8 41 36 fa dc 06 69 bb 3c e4 10 34 27 09 eb b3 |.A6...i.<..4'...|

00000080 66 e3 ec 97 ea ae 23 ff fe 8e a0 00 6a cc 50 eb |f.....#.....j.P.|

00000090 2d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |-.......P.......|

000000a0 4c 5a 49 50 01 0c 6d 2a 1a 08 a2 03 25 66 f1 4b |LZIP..m*....%f.K|

000000b0 78 c5 a2 05 ff 2e e6 d9 d2 20 1a ad 34 f8 e2 1d |x........ ..4...|

000000c0 e8 41 36 fa dc 06 69 bb 3c e4 10 34 27 09 eb b3 |.A6...i.<..4'...|

000000d0 66 e3 ec 97 ea ae 23 ff fe 8e a0 00 6a cc 50 eb |f.....#.....j.P.|

000000e0 2d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |-.......P.......|

000000f0 4c 5a 49 50 01 0c 61 2a 1a 08 a2 03 25 66 f1 4b |LZIP..a*....%f.K|

00000100 78 c5 a2 05 ff 2e e6 d9 d2 20 1a ad 34 f8 e2 1d |x........ ..4...|

00000110 e8 41 36 fa dc 06 69 bb 3c e4 10 34 27 09 eb b3 |.A6...i.<..4'...|

00000120 66 e3 ec 97 ea ae 23 ff fe 8e a0 00 6a cc 50 eb |f.....#.....j.P.|

00000130 2d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |-.......P.......|

00000140 4c 5a 49 50 01 0c 72 2a 1a 08 a2 03 25 66 f1 4b |LZIP..r*....%f.K|

00000150 78 c5 a2 05 ff 2e e6 d9 d2 20 1a ad 34 f8 e2 1d |x........ ..4...|

00000160 e8 41 36 fa dc 06 69 bb 3c e4 10 34 27 09 eb b3 |.A6...i.<..4'...|

00000170 66 e3 ec 97 ea ae 23 ff fe 8e a0 00 6a cc 50 eb |f.....#.....j.P.|

00000180 2d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |-.......P.......|

00000190 4c 5a 49 50 01 0c 6b 2a 1a 08 a2 03 25 66 f1 4b |LZIP..k*....%f.K|

000001a0 78 c5 a2 05 ff 2e e6 d9 d2 20 1a ad 34 f8 e2 1d |x........ ..4...|

000001b0 e8 41 36 fa dc 06 69 bb 3c e4 10 34 27 09 eb b3 |.A6...i.<..4'...|

000001c0 66 e3 ec 97 ea ae 23 ff fe 8e a0 00 6a cc 50 eb |f.....#.....j.P.|

000001d0 2d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |-.......P.......|

000001e0

The Linux kernel’s MicroLZMA variant, used by EROFS, also re-purposes this always-zero initial byte.

Next: Part 2: A Complete Toy Range Coder.

Published: 2024-04-14